Technology

In the decade since it commenced, the Virtual Angkor project has evolved organically to encompass new technologies and approaches in an effort to present a comprehensive reconstruction of the city and its inhabitants.

What does it mean to ‘model’ a historical city? For many digital heritage projects, the starting point is an obvious one: modeling architecture. The first model we made was not a reconstruction of an archaeological site but an animated character. It was one that featured prominently in Angkorian art and iconography, but it was neither a person, a god nor a mythological being. Instead it was an elephant. In the years after the completion of the first elephant, we modeled and remodeled the 3D anatomy of the people of Angkor, their ornaments, their attire, the objects that they carried, and the vehicles that carried them.

As we crafted more characters, it became necessary to draw in objects scattered beyond Angkor to situate them in the virtual world. There is a remarkable collection of Angkorian bronze statuary and status items maintained in museums and galleries around the world. Once scanned, these artefacts were digitally repatriated from museum displays and archives and then merged with the array of Angkorian 3D models we had already assembled. With these characters in hand, we started to approach modeling the rest of Angkor; the roads, the canals, the rice fields and the wooden dwellings that once comprised the vast city of Angkor.

At Angkor, the ruins of temples have long served as focal points of scholarly interest and investigation. We were interested however in the spaces surrounding the temples, both inside the extensive laterite walls and outside the temple moats, where many of Angkor’s 750,000 inhabitants would have lived their lives. To see the living city, however we needed help from a different data set beyond the surviving structures. We relied especially on extensive archaeological mapping conducted by the University of Sydney’s Greater Angkor Project and the EFEO (Evans, Pottier et al. 2007).

In 2014, we transitioned away from constructing 3D scenes built to render single images and animated sequences and began importing all of our models into Unity. It was around this time that the scope of the project broadened considerably as we were able to instill the animated figures with dynamic behaviors. The result has been to create an expansive virtual environment. What is clear, however, is that the process of modeling Angkor in virtual reality has no definitive end. For more details see the article below:

Adam Clulow and Tom Chandler, “Modeling Virtual Angkor: An Evolutionary Approach to a Single Urban Space,” IEEE Computer Graphics & Applications, Volume 40, Issue 4 (2020), 9-16

Simulation of 24 hours in Angkor Wat

The first application is a simulation of a 24-hour cycle at Angkor Wat that aims to visualize the complex’s daily operation almost a millennium ago. Current archaeological estimates suggest that at its peak, the Angkor Wat complex, was serviced by a workforce of over 20,000 that were in turn supported by a population of up to 125,000 people.

Whereas historians typically model events over years or centuries, the time frame for our simulation, – 24 hours or literally one day in the life of the complex – is both more compressed and more familiar. It features a large population of autonomous ‘agents’, that is our original animated characters, following path finding (A*) algorithms.

We divided the agents into four broad categories; visiting elites and their retainers, residents, commuting workers, and suppliers. All agents are guided by broadly similar rules, though each agent category is given a different agenda in navigating the space of the city.

Interactive, navigable virtual map

The second application is an interactive, navigable virtual map of Greater Angkor that extends over almost 3500 square kilometers. This multilayered visualization incorporates LiDAR data, digital elevation (DEM) files, and GIS mapping layers.

We effectively ‘peeled off’ layers from this geospatial archive of cultural and natural features in the Angkor area – ponds, canals, occupation mounds, temple sites and rice fields – and translated them into bitmaps, with each map informing the distribution of 3D models above it.

The key data source for our virtual map of Angkor was a geospatial repository maintained by the University of Sydney and the EFEO. This is a comprehensive resource, resolving features from the landscape scale down to the level of individual households and artefacts in the archaeological record. It aggregates a century and a half of historic maps and the results of various archaeological survey and mapping campaigns since the 1990s.

Virtual reality experience

The third application is a virtual reality experience of Angkor. Here we have adapted the cartography of the virtual map around the VR viewer. Once inside the VR headset, you can walk through the map, with the city stretching out roughly at waist level. Leaning down near to the landscape prompts a peal of location-based soundscapes, all based on field recordings, emanating from the temples, roads and fields. Mixed in among these sound files are the recordings of reconstructed Angkorian instruments that have been created by ethnomusicologist Patrick Kersale based on evidence in the bas reliefs of instruments that have long since vanished from Cambodia, and indeed wider Southeast Asia.

The ‘x-ray’ aesthetic of the opening map mimics the way that LiDAR scans the landscape for hidden features, but our reconstruction process effectively reverses LiDAR technology. The 3D models that are visible on the map denote the virtual reconstructions of Angkor that we have extrapolated upon, or assembled ‘on top’ of the LiDAR data. The result is a visualization of living city of Angkor growing out of its archaeological imprint. Using a controller, the VR user can select animated markers which transport them to scenes of daily life at ground level.

AI and Angkor: Possibilities and Perils

One of the most common questions we’re asked is about the role of AI in the broader Virtual Angkor project. The short answer is that Virtual Angkor is the product of more than a decade of collaboration among historians, archaeologists, and 3D modelling specialists from around the world. Every part of this website and the virtual environment has been painstakingly crafted by hand, grounded in years of rigorous research and expert analysis.

However, Virtual Angkor uses a specific kind of artificial intelligence called “game AI.” This is different from “generative AI,” which is what most people think of when they imagine what an AI might do. Game AI is an older form of AI and is used in this project to lead the modeled crowds to seek out paths and simulate other such basic behaviors. It acts as a character’s “brain” and is the result of each character being given simple rules governing where a character can go and what actions is can perform. This AI is fully contained by the project and only exists when we tell it to run.

On the other hand, AI tools have emerged that can generate text and images with remarkable speed in recent years. For example, entering “Angkor” into an AI image generator might yield visually striking and seemingly accurate results. But while AI can impress, it also comes with serious limitations, especially when it comes to representing complex historical realities.

Explore the activity below to better understand what AI gets right, what it gets wrong, and why human expertise still matters.

Prompt: Image of Angkor in the 13th Century

You might have noticed a few issues. For example, note the broken tower on the right side of the complex. If this was the heyday of Angkor, why would a spire be broken? Additionally, this image shows the color scheme of the complex as it appears today: monochrome and sand colored. However, according to Zhou Daguan’s contemporary description of Angkor, the complex was decorated with painted and gilded plaster, as shown in the Virtual Angkor recreation. The AI-generated image is also particularly problematic when it comes to representing sacred spaces and who could or not could enter certain parts of the wider city. Do you notice any other inconsistencies?

To learn more about the physical appearance of the Angkor Wat complex, see the teaching module Power and Place.

Prompt: Cambodian Noble on an Elephant

Examine this AI-generated image created with the prompt of “Cambodian noble on an elephant.” Once you have thoroughly examined it, click the image to reveal a similar model created by the Virtual Angkor team. What are the similarities? What are the differences?

The AI-generated image looks good at first glance but dig deeper and you will find multiple inaccurate elements. The broad strokes and themes capture the essence of elite authority at Angkor, including the elephant, the setting, and the posture, but once you examine the details, the integrity of the image falls apart. The clothes are drawn from the 18th and 19th century Siamese and Cambodian court dress, not 14th century Angkor. Additionally, elites like the one depicted here would not have ridden elephants by themselves. Rather they would have been served by an elephant handler and entourage, as seen in the Virtual Angkor recreations.

To learn more about how Angkorian royalty, see the teaching module Power and Place.

Prompt: Interactions with Water

Examine this AI-generated image created with the prompt of “How residents around twelfth century Angkor Wat interacted with the water and climate.” Once you have thoroughly examined it, click the image to reveal a similar model created by the Virtual Angkor team. What are the similarities? What are the differences?

The image created by ChatGPT misrepresents this prompt in a number of ways. Compare the size and style of canoes between the AI generated image and the representation created by Virtual Angkor. Additionally, the moat surrounding Angkor Wat was 13 feet deep: people would not be able to wade in it. Beyond this, it is incredibly unlikely that the moat was used for rice cultivation, as shown in the AI-generated image. Finally, the Angkor Wat complex seen in the background of the AI-generated image is monochrome, a historical inconsistency explained earlier.

To learn more about how Angkorians interacted with the water, see the teaching module Water and Climate.

Prompt: Marketplace in 12th Century Angkor

Examine this AI-generated image created with the prompt of “A market in twelfth century Angkor.” Once you have thoroughly examined it, click the image to reveal a similar model created by the Virtual Angkor team. What are the similarities? What are the differences?

In comparing these two images, we can see that the one created by the Virtual Angkor team is much more historically accurate. Stalls in the marketplace would likely have had thatched roofs over cloth roofs. The marketplace would also not be adjacent to the Angkor Wat complex and rather a little bit down the road. Finally, as mentioned previously, the complex of Angkor Wat itself was not monochrome in its heyday, rather its spires would be decorated with paint and plaster.

To learn more about the goods in Angkorian marketplaces, see the teaching module Trade and Diplomacy.

Behind the Scenes

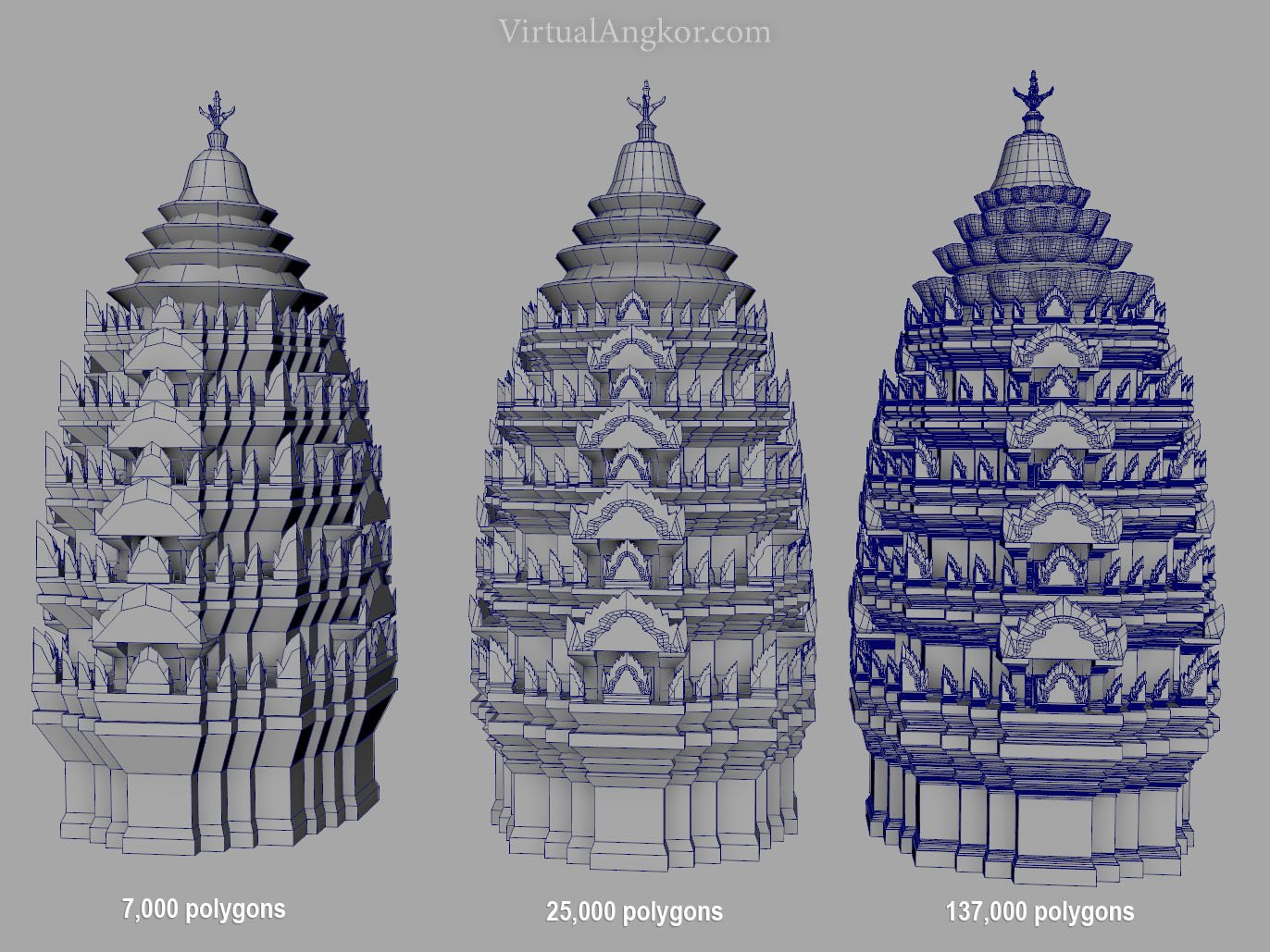

Below, you can see some examples of how the Virtual Angkor team creates the scenes shown on the site. Each figure is composed of wireframes, wihch are then used as the “skeleton” for a 3D-rendered model.