Theme Two: Goods and Exchange

Aside from being an important source of natural products for China, Angkor also served as an important export market for Chinese manufactured goods, particularly ceramic and glass products. Surviving fragments of pottery and glass products found in Angkor have been crucial in demonstrating the involvement of Khmer elites in broader Southeast Asian maritime networks that connected the region to an international economic system dominated by trade. Read the excerpt from Zhou Daguan’s A Record of Cambodia, the paper by Aedeen Cremin and the article from Carter, Dussubieux, Polkinghorne and Pottier and answer the following questions.

Readings

Excerpts from Zhou Daguan's A Record of Cambodia: The Land and Its People

Sought-After Chinese Goods

They do not produce gold or silver in Cambodia, I believe, and so they hold Chinese gold and silver in the highest regard.

Next they value items made of fine, double-threaded silk in various colors. Next after that they value such things as pewter ware from Zhenzhou, lacquer dished from Wenzhou, and celadon ware from Quanzhou and Chuzhou, as well as mercury, cinnabar, writing paper, sulphur, saltpetre, sandalwood, lovage, angelica, musk, hemp, yellow grasscloth, umbrellas, iron pots, copper dishes, glass balls, tung tree oil, fine-toothed combs, wooden combs, and needles – and of the ordinary heavier items, mats from Mingzhou. Beans and what are particularly sought after, but they cannot be taken there.”

See also:

“The magnitude and variety of China’s ceramic trade are becoming increasingly clear through the meticulous work of archaeologists in China and Southeast Asia (summarised in Needham 2004). At Angkor, around 1300, Zhou Daguan had noted that the Chinese goods most in demand were ‘gold and silver, then light-mottled double-threaded silks. After these come tin goods from Zhenzhu, lacquered trays from Wenzhu, green porcelain from Quanzhou and Chuzhu’ (section 21, Smithies 2001: 63). Archaeology confirms the popularity of Chinese imports: during a quarter-century of fieldwork, from 1949 to 1974, Bernard Philippe Groslier, the last French Conservateur at Angkor, said he had excavated ‘literally thousands’ of Chinese sherds (1981: 225).”

“Although glass beads were found in large quantities in Southeast Asia during the Iron Age and into the first millennium CE, glass artifacts from the Angkorian period (ninth–fifteenth centuries CE) are less common and have not been as well-studied. This paper presents the results of an analysis of 81 glass beads and artifacts from the ninth-century royal capital of Hariharālaya and later (twelfth–fourteenth centuries CE) contexts from the walled city of Angkor Thom. Compositional analyses using laser ablation– inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) have identified glass belonging to three broad compositional groups. The earlier Hariharālaya sites have numerous glass beads and vessel fragments made from vegetal soda glass, associated with Middle Eastern production, as well as high-alumina mineral soda glass of a sub-type frequently found at Iron Age sites in Southeast Asia and likely produced in South Asia. Beads from the later-period sites within Angkor Thom are primarily lead glass, associated with Chinese glass production, and different sub-types of high-alumina mineral soda glass that have also been found at sites in Southeast Asia dating from the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries CE. A small number of beads from Angkor Thom also have a vegetal soda composition distinct from beads at Hariharālaya. The results of this study provide a new type of evidence for elite participation in broader regional exchange networks during the Angkorian period.”

Questions

What kind of Chinese goods did Khmer consumers want from Angkor? Why do you think they desired these items? What kind of significance do you think these goods had in Khmer society?

According to the articles, when did the relationship between Angkor and China begin to intensify? How have archaeologists come to this conclusion?

What evidence do Carter, Dussubieux, Polkinghorne and Pottier use to demonstrate that the Khmer Empire were part of a broader regional network of trade? What other polities were involved in this network?

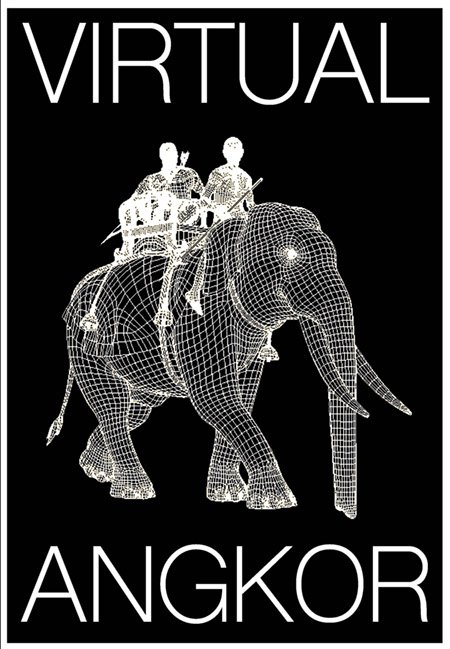

Examine the images below or proceed directly to the next lesson in the module.